I have a window of opportunity (that is to say, a sleeping baby) and I had an entirely different blog planned (fear not, it will make its appearance soon). But I keep getting messages about Diwali, the Indian festival of lights, and I am not one to ignore summons from the universe.

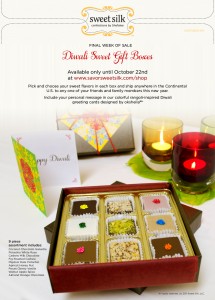

First, a few weeks ago Sweet Silk, my favorite online Indian confectionary shop started emailing me messages reminding me to order sweets for my sweets–the traditional gift made to friends and relatives at this time. I’d post a link to their Diwali wares, but they’ve been removed from the site; the five-day festival started yesterday, so it’s too late to order. (But really, if you celebrate Diwali, you don’t need me to remind you, do you?)

Then, I got a photo via text of my BFF’s daughter all dressed up for Diwali. One can’t go around posting photos of other people’s children to the internet (unless one is said child’s grandmother) so you’ll have to use your imagination, but trust me, it was the cutest thing ever, and the little lady knew it–she had a big old smile on her face!

Finally, I saw this gem of a photo on Facebook and I knew I had to scrap all my plans and get on the Diwali bandwagon. And so I say, let there be light.

The name Diwali comes from the Sanskrit word for “row of lamps”, as the festival involves lighting said lamps (and now electric lights as well) for a number of reasons. The first is rooted in Hindu mythology: the lights are meant to welcome the god Ram back from his unjust banishment in the forest for 14 years, to celebrate his triumph over the demon Ravana, and to herald the beginning of his reign of just, good rule, a period of prosperity for all in his kingdom. The same lights also welcome Laksmi, goddess of prosperity, into the home of those who chose not to curse the darkness, but instead, lit a candle.

Diwali is celebrated by Hindus, but also by Jains and Sikhs, even some Buddhists, which is why I referred to it as an Indian festival, not just a Hindu celebration. For all who observe it, the lights of Diwali indicate a triumph of good over evil, not just Rama’s victory over Ravana, but the victory of the good within each of us over our own baser instincts. So that’s the second, more psychological reason for the lamplight.

It sometimes seems to me there’s a movement now in certain schools to tamp down any religious observances for fear of offending those who don’t practice a given faith. But when I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, the prevailing operating system, at least in the small New England private school I attended, was to celebrate all of them, a big old potpourri of partying. Needless to say, I loved it. And the biggest pan-religious celebration of them all fell around the holidays and was billed as a cross-cultural celebration of the festival of lights. The theory was, everyone’s got a festival of lights: Hannukah. Diwali. Christmas (candles lit in the window and on the heads of Swedish girls dressed as Saint Lucia whose parents weren’t as fussy about fire safety as some of our folks). Kwanzaa with its seven candles.

That was about all we covered back in the day, but if you think about it, the impulse to create light out of darkness stretches deep and wide across cultures. Just look at firecrackers at Chinese New Year (meant to scare away evil, just like the firecrackers set off at Diwali).

Still, I didn’t realize until just now, looking into Diwali, that the yearning for light during the longest, darkest nights of the year isn’t just borne out of our deep-seated shared pyromania. It’s also an act of hopefulness that we will all strive to light the world with our best selves instead of giving into our darker sides.

As the photo of illuminated India shows, when it comes to celebrating, the dominant theory on that subcontinent is go big or go home. This is one of many aspects of Indian culture that so appeal to me; sometimes, more IS more. And while there is a spare beauty in a Quaker meetinghouse, for example, having grown up in the Orthodox church, surrounded by incense and bearded priests in golden robes, and candles singing the tips of my braids at midnight on Easter, I love me a lavish explosion of light and color.

So I think we should all celebrate Diwali at some point between now and October 3oth, when this year’s festival ends (and those of us observing Halloween prepare to stare bravely at each other’s demonic darker sides). Maybe it’s as simple as meditating on the good in the people around us as we light a candle (as opposed to hoping the scent will cover up the smell of breast milk and poo in the nursery/guest room, which is what I did last time I lit a match). Or maybe, like a good observer of Diwali, that means putting on auspicious new clothes and spreading joy to our loved ones and light to our community. However you do it, shine on. Even if, like me, your auspicious new clothes are all covered in spit-up.